In this post, I want to talk about two aspects of photography that I believe are absolutely essential: composition and storytelling.

Let’s start with composition.

Composition is one of the few areas in photography where we have complete control. It’s where we can truly add something unique and personal — our way of seeing the world. But composition is more than just arranging shapes and lines in a pleasing way. It’s also about how we use colour, tone, and light to guide the viewer’s eye through the image. I see the use of colour and tones along with lines and shapes as all part and parcel of composition.

I like to think of composition as design — the design of a photograph. How do all the visual elements fit together? How do they work as a whole? Good composition is about what some people might describe as harmony: the way shapes, lines, tones, and colours interact to create balance, rhythm, and flow.

Now the second aspect: storytelling.

When I talk about storytelling in photography, I don’t necessarily mean showing a literal story. It’s not always about a clear narrative wihin the frame. Often, it’s about creating a sense of story, or hinting at a story — something that feels like there’s more happening beneath the surface. You can’t always explain it, but you sense it.

That subtle uncertainty is powerful. It invites the viewer in. It makes them curious and encourages them to use their imagination. For me, that’s what makes an image memorable — when it leaves space for interpretation rather than spelling everything out. If a photograph is too literal or obvious, it can end up feeling a bit contrived.

So, composition and storytelling — those are the two areas I’m constantly thinking about and practicing in my own photography (and failing most of the time).

But there’s another layer to all this — something about how we talk about photography itself.

When we try to explain concepts like composition or storytelling in words, we often end up simplifying something that’s deeply intuitive. Language helps us communicate ideas, but it can also trap us in definitions and formulas. Photography, at its core, is a visual language, not a verbal one. It’s something we need to feel rather than explain.

The moment we try too hard to define what composition “should” be or how a story “should” be told, we risk losing the magic. Creativity doesn’t live in rules — it thrives in openness and curiosity.

Maybe we need to loosen our grip a little. Instead of trying to control every element or chase a perfect formula, we can allow ourselves to respond emotionally to the scene in front of us. When we do that, photography becomes a kind of dialogue with the subconscious — a way of discovering parts of ourselves we didn’t know were there.

So perhaps what I’m really saying is this:

Let’s bring the mystery back into photography.

Let’s make it less about certainty and more about emotion, intuition, and imagination.

Let’s move away from rigid rules and embrace photography as something deeply human — something we feel our way through.

Tag: art

-

Composition and Storytelling: And a Sense of Mystery

-

Layers of Interest in a Photograph

Picking up from my last post, I’ve been thinking more about what makes a photograph interesting — and in particular, about the idea of layers of interest. We can be drawn to an image for all sorts of reasons, but I want to focus on some of the more direct, obvious qualities that make a photograph work.

The First Layer: The Subject Itself

The most immediate layer of interest is the subject. Is it inherently interesting? Does it draw attention simply because of what it is — regardless of how it’s been photographed? This is when we think of a photograph as being of something. Some subjects have an innate visual or emotional pull — a dramatic sky, a face full of character, a fleeting gesture — and that alone can make a photograph compelling.

The Second Layer: Design and Composition

Another layer of interest comes from how the photograph is designed. How has the photographer composed the image? What has been included or left out? A well-composed image can feel balanced, satisfying, and beautifully arranged.

I often think of this layer as using the scene in front of you as raw material for design. The interesting question, though, is how much that design reflects what was actually there — and how much it transforms it. Does the composition help me experience the scene more deeply, or does it pull me away from it? Does it reveal the reality of what I saw, or does it impose something artificial on top of it?

The Third Layer: Meaning and Emotion

Then there’s a deeper, more psychological layer — the one that deals with meaning. This is where metaphor, story, and emotion come into play. It’s what the photograph means rather than just what it shows.

At this level, I’m interested in the relationships within the image — between people, objects, or ideas — and in the emotions they evoke. Sometimes this layer is very direct, like the expression on someone’s face. Other times, it’s subtle, hidden in atmosphere, symbolism, or mood.

The Fourth Layer: Audience and Context

Of course, even if a photograph has a fascinating subject, a strong design, and emotional depth, that doesn’t necessarily mean people will appreciate it. Whether a photograph is seen as “good” depends so much on the audience and the context in which it’s viewed.

History is full of examples of art that was misunderstood or dismissed at first, only to be admired years later. The context of viewing — who’s looking, where, and when — can make all the difference. Finding an audience that connects with your work can be one of the hardest parts of being a photographer.

A picture that leaves people cold isn’t necessarily a failure. It might simply be waiting for the right audience — or the right moment — to be understood.

Communication and Value

I sometimes think that one of the most interesting questions about art is not whether it’s good in any absolute sense, but whether it communicates. If we see all creative work as a form of communication — and not every artist does — then perhaps the real test of value is how effectively it reaches people.

If a piece of art moves people, starts conversations, or even sells for millions, it’s clearly connecting on some level. In that sense, dismissing it as “rubbish” misses the point if its purpose is to communicate and be appreciated.

So maybe the value of a photograph doesn’t just lie in its subject, design, or meaning. Maybe it also lies in the way it speaks to others — or even just in the fact that it speaks at all. -

Seeing with the Imagination

Hello — this is a quick post to capture a few thoughts before they get blown away by the winter winds.

One of life’s great joys for me is visiting exhibitions, especially art exhibitions. I was thrilled recently to visit Cartwright Hall in Bradford to see the four shows from this year’s Turner Prize shortlist. Then, of course, there’s the annual Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy — always a highlight — and closer to home, one of my favourite places is the Mercer Gallery in Harrogate.

I mention all this because I believe art can be deeply inspiring for photographers — and not just the visual arts.

Recently, I was listening to an interview with Philip Pullman, author of His Dark Materials. He said something that stayed with me: that it’s important to see with the imagination. There are things we can’t see with the naked eye — whole worlds that exist only when we engage our imagination. And those worlds, he said, are no less real.

When you talk to artists, you quickly sense what moves and excites them — what drives them to create. Their work comes from the imagination, is expressed through imagination, and ultimately, it takes imagination to interpret it.

Something I’ve noticed over time is that for many artists, the subject itself is often less important than the feeling the work creates — what it evokes in the viewer. They think in terms of colour, shape, line, and texture: the visual elements that carry emotion. Often, the subject is subtle, even withdrawn from the scene, inviting the viewer to work a little to uncover its meaning.

Photographers, on the other hand, often take a different approach. We tend to focus on clarity — on the placement of the subject, the focal point, and where the viewer’s eye is being directed. Painters seem far less concerned with such precision. They work more through intuition and mystery, treating patterns, shapes, lines, colours, and textures as subjects in their own right. These elements are often what the work is really about — more so than simply depicting an object and placing it neatly within a frame.

That’s not to say a clear subject isn’t important in photography, but perhaps the starting point could be the design — or even the feeling — rather than just the object itself. The subject might just as easily be light, atmosphere, or emotion.

This is only a brief reflection, but it raises a question: do our familiar photographic formulas — with their emphasis on clarity and defined subjects — sometimes limit our imagination? Could the unseen elements in an image be just as important as the ones we include?

As Philip Pullman suggested, can we “see through” a picture with the imagination? Perhaps what we leave out is every bit as significant as what we show. -

The Three Circles of a Great Photograph

This post is part of my ongoing exploration into what makes a great photograph. Lately, I’ve been asked to judge a few photographic competitions, which has really made me think about how we decide what makes one image stand out over another. To do that fairly, you need some kind of framework—a way to explain why certain photos deserve recognition. The tricky part is keeping those criteria simple enough to communicate, but broad enough to work across all the different styles and approaches you see in a competition. You have to think about things like technical ability, composition, and creativity—each of which is a deep subject on its own. And, of course, there’s always that tension between judging something “objectively” and knowing that, in the end, photography is a deeply subjective art.

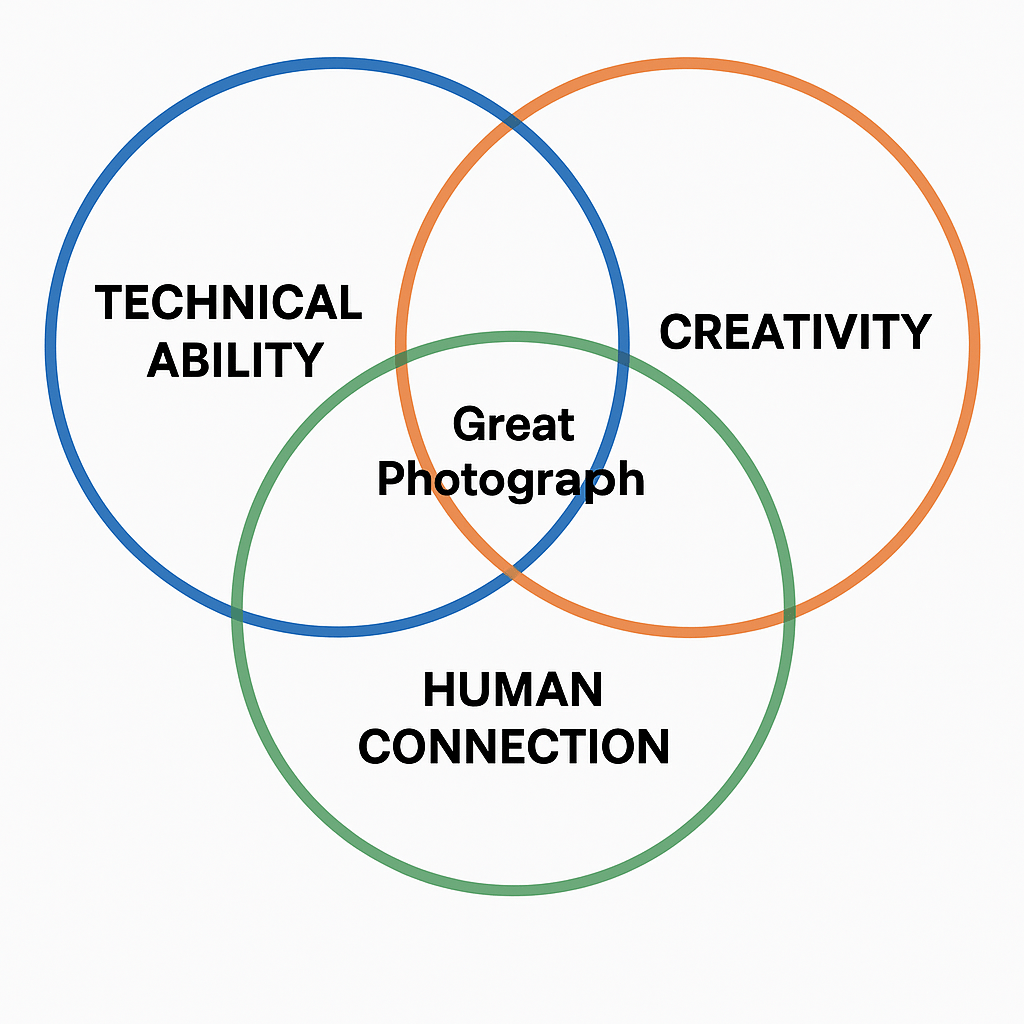

When we think about what makes a great photograph, I believe we can draw three overlapping circles — each representing a vital dimension of photographic excellence. Together, they form a kind of Venn diagram for understanding not only how we take photographs, but how we create meaningful visual art.

1. Technical Ability

The first circle is technical ability — the craft of photography. This includes mastery over the camera: control of lighting, exposure, focus, and all the technical elements that produce a good image. Composition also belongs here — the ability to use framing, scale, depth, and perspective to lead the viewer’s eye and communicate a sense of balance or drama.

Technical ability ensures the photograph “works.” It’s the part of photography most often emphasized in competitions and camera clubs, where the precision of exposure or sharpness of focus is often rewarded. Many photographers take their inspiration from others and adopt well-known techniques, producing technically excellent but familiar images.

There’s nothing wrong with that — but it’s only one circle.

2. Creativity and Originality

The second circle is creativity. Creativity goes beyond technique; it’s the spark of originality that brings something new into the world. It’s about experimentation, expression, and authenticity — the photographer’s ability to translate their own way of seeing into an image that feels fresh.

Originality isn’t about novelty for its own sake, but about personal insight. A creative photograph makes us pause and think, “I haven’t seen it like that before.” It’s that sense of discovery that keeps photography alive and evolving.

This circle can exist independently of technical mastery. Experimental and playful photography often thrives precisely because it breaks the rules. But when creativity and technical ability meet, something special happens — images that are both well-crafted and deeply original.

3. Human Connection

The third circle is the most vital and perhaps the most neglected: human connection. This is the power of a photograph to move us — to evoke emotion, empathy, or even challenge our beliefs.

A great photograph doesn’t just show something; it makes us feel something. That emotional or intellectual spark connects photographer and viewer in a shared human moment. It might be joy, sadness, curiosity, or wonder — but it’s that connection that gives photography its lasting power.

This is the circle where photography becomes more than craft — it becomes art.

The Overlap: Where the Magic Happens

Each of these circles can exist on its own. Technical photography might serve science or documentation — precise, accurate, and emotionally neutral. Creative photography might be exploratory or conceptual without technical polish. Photographs that focus purely on emotional connection might be spontaneous or imperfect, yet deeply moving.

But in the overlap — where all three circles meet — we find the truly great photographs.

These are images that are well-made, original, and emotionally resonant. They don’t just record the world; they reveal it anew.

Artificial Intelligence and the Human Touch

In the age of artificial intelligence, this third circle — human connection — becomes even more crucial. AI can now simulate technical ability and even mimic creative styles, but it struggles to convey genuine human emotion or imperfection.

This should prompt us to ask: What makes a photograph truly human?

Perhaps it’s the trace of the artist’s hand — the momentary decision, the emotional vulnerability, the imperfection that reveals authenticity.

Rather than competing with AI for flawless production, photographers might lean into what makes us distinct: our ability to feel, to respond, to connect.

In the future, photography that bears the mark of a real person — expressive, imperfect, emotional — may stand out as the most valuable of all.

© Mark Waddington 2025

-

Why Authenticity and Originality Matter in Photography

A photograph is never just about what’s in front of the lens. It’s also about the person behind it—their way of seeing, their choices, their experiences. When we look at a photograph, we’re not only seeing a subject, we’re also catching a glimpse of the photographer’s personality and intentions. That’s part of what gives an image its energy and life.

It helps, then, to know something about the photographer. A bit of context—who they are, where they’ve been, what they’re trying to say—can deepen our connection to the picture. It can also help us decide how much we trust it as an expression of truth.

Truth, of course, is especially important in documentary photography. But truth is not always easy to pin down. Even before artificial intelligence, photos could be staged, cropped, or stripped of context. Roger Fenton, one of the earliest war photographers, even carried a portable studio into the field. In one famous Crimean War image, cannonballs appear scattered across a road. Historians have long debated whether he placed them there himself—a reminder that questions about authenticity in photography are nothing new.

The rise of misinformation has made these questions even more urgent. Images and stories circulate faster than ever, often manipulated or detached from their original context. Audiences now need stronger media literacy to separate fact from fabrication.

This is why trust in named photographers and reputable news agencies matters so much. Our tradition of trusted journalism—such as the BBC—remains a vital safeguard. But the threat misinformation poses to democracy is real. Photographers and journalists carry the responsibility to represent events truthfully, and viewers share the responsibility of reading them critically. Truth in media is a collective task: without it, free speech risks losing its meaning. Agencies that cut corners with integrity won’t last long, because audiences must feel that the work they encounter comes from people who take truth seriously.

Looking ahead, I suspect there will be a growing reluctance to over-process or over-dramatise photographs, precisely because of fears they could be mistaken for AI fabrications. When we look at a landscape, we’ll want the colours and atmosphere to feel believable. When we see a portrait, we’ll value signs of humanity—the imperfections, the individuality—over artificial polish.

AI-generated images will always be built from patterns in existing material. That doesn’t mean they aren’t interesting, but it does mean the real challenge for artists will be to express something that feels truly original, rooted in lived experience.

In this sense, AI may turn out to be a useful reminder. It could sharpen our awareness of what makes human expression so compelling. The best photographs will still be those that carry something no machine can invent: a lived emotion, a unique story, a way of seeing that could only have come from one person, in one moment, in one place.

© Mark Waddington 2025