I’ve been thinking a lot about one of the most important qualities a photograph needs if it’s going to be noticed and make its way in the world: impact.

It’s the starting point for most photo competitions, and it’s often the first thing people respond to when scrolling online.

But impact isn’t straightforward. I struggle with it, because the kind of work I really love often reveals itself slowly—the sort of photograph you hang on your wall and grow to appreciate more and more over time. That’s a slow burn, not a quick hit.

The more I reflect, the more I realise that impact comes in different forms. It doesn’t always mean a punch in the gut or a visual assault. Sometimes it’s subtle, nuanced, and it unfolds gradually. The challenge is that we live in a culture where images flash by at lightning speed. Judges, social media users, and casual viewers all make split-second decisions.

In competitions especially, clarity of intent matters. A photograph needs confidence—it should be clear what the subject is and where the viewer’s eye is meant to land. Try this exercise when scrolling through social media: ask yourself, What’s this photograph really about? Where am I being directed to look? You’ll be surprised how often the answer isn’t obvious. Without that sense of direction or intent, an image struggles to hold attention.

And attention is scarce. It’s said we see up to 10,000 images a day across the internet, TV, magazines, and advertising. Who knows how accurate that number is, but it feels believable. Most of those images disappear without trace. Which raises the question: why do we even take photographs?

Competitions give one answer. The judging process often starts with a quick scan: images might go into piles of “possibles,” “maybes,” and “rejects.” Only the possibles and maybes get a closer look. So yes, an image has to have presence—impact, appeal, engagement—whatever word you prefer.

In advertising, I have heard the term “blink test” used: if someone hovers over an image for more than three seconds, it passes. Just three seconds to earn a second look. That’s why the internet pushes forward extreme content—violence, sex, or cute animals—because they stop the scroll. Think of recent “blink-worthy” photos: burning police cars, riots, or Donald Trump with his fist raised and bloodied face. These are images engineered to grab attention, and AI could well be used to ensure they’re the ones we see most often. On platforms like X, truth matters less than clicks. That’s the blink factor at work.

In this climate, impact becomes essential—not just for competition success but for survival in a saturated visual culture.

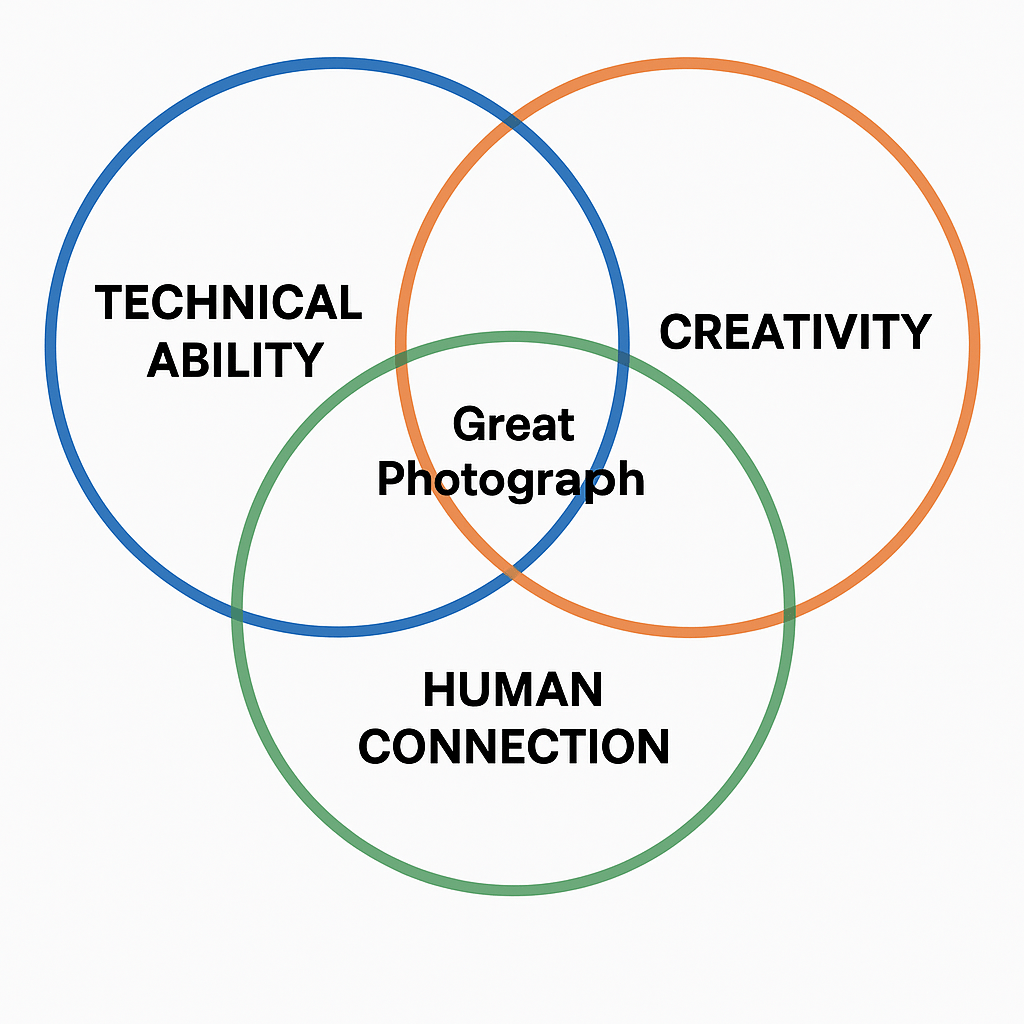

So what do we actually mean by impact, and where does it come from?

Looking at competition archives like those of the Photographic Alliance of Great Britain, certain patterns emerge. Impact might come from the drama of a sporting moment, the grandeur of architecture, a portrait that reveals character, or a landscape lit in a way that makes it sing. But here’s the real question: does the impact lie in the subject itself, or in how it’s photographed?

You can, after all, take a perfectly ordinary photo of an impressive subject, or, perhaps, an impressive photograph of a very dull subject. But in competitions, judges usually want to see the hand of the photographer—the sense that someone has shaped the image, brought their own experience to it. Authorship matters. Otherwise, you end up in murky territory, like the famous “chimpanzee selfie,” where the camera’s owner claimed authorship of a photo the animal technically took.

Different genres demand different skills. Photojournalists are judged primarily on access and storytelling, while landscape photographers might be evaluated on composition and presentation. But across genres, impact always comes down to the viewer. No viewer, no impact. And even when there is a viewer, their response depends on whether they’re open to what the photograph offers.

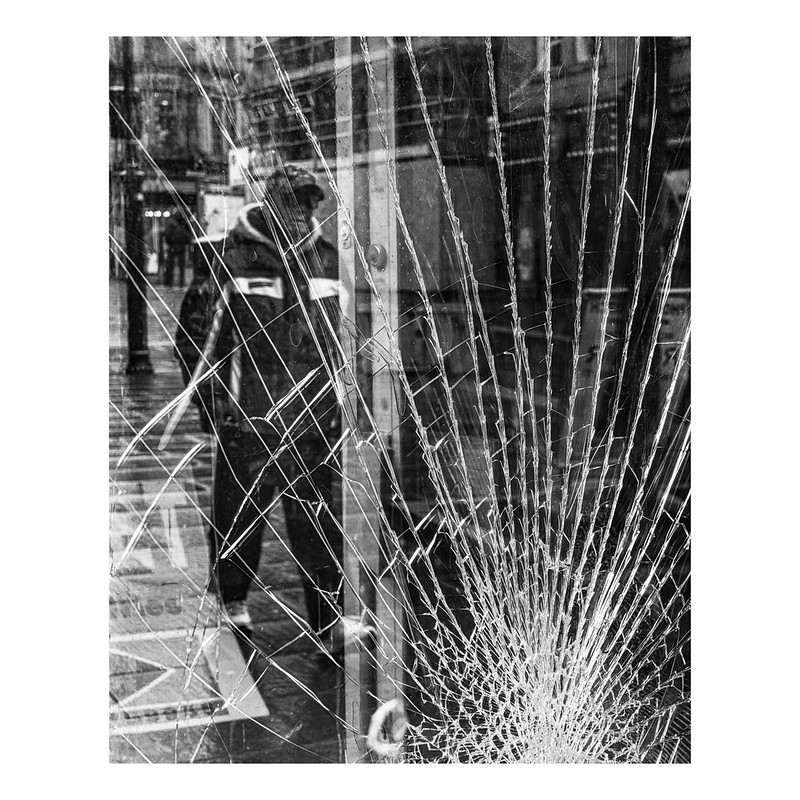

That’s tricky in today’s oversaturated world, where familiar views quickly become clichés. How many photos have we seen of Dunstanburgh Castle or the Old Man of Storr? I love those places, but sometimes I don’t even bother taking my camera out because I’ve seen the same view too many times. The challenge is to make something familiar feel fresh—and that doesn’t come from gimmicks or heavy editing. It comes from lived experience.

Impact is really about emotion being transferred from photographer to viewer. It’s the photographer saying, This is what I saw, and this is how I felt about it. If that excitement is genuine, it carries through. If it’s contrived—wrinkles on an elderly person exaggerated in black and white, or a dull sky made unusually dramatic with Lightroom sliders—it can feel wrong.

That’s why original experience is so important. Many people today live secondhand, scrolling through social media and absorbing other people’s ideas whats hot and what’s not. If photography is to stand as a serious art form, it has to come from direct experience—what the photographer actually saw and felt. Passion is a good word for it. Does the image communicate passion for the subject?

That passion can come through in unexpected ways. While iconic landmarks risk overexposure, everyday subjects can surprise us. Think of Vivian Maier’s New York street scenes or Edward Weston’s photographs of cabbage leaves—ordinary things made extraordinary through attention and care.

Ultimately, photography is as much about presence as it is about timing—being there, being attentive, and being excited.

Great portraits don’t just record faces; they capture relationships. Great landscapes don’t just show a place; they reveal how it felt to be there. The best photographs usually come with a story, they change what we think, feel and believe.

© Mark Waddington 2025